About Me

Arpana Caur, a

Contemporary Indian Artist was in

born 1954. She is a distinguished Indian painter and has been exhibited

since 1974 across the globe. Her solos apart from Delhi, Mumbai,

Calcutta, Bangalore and Chennai have been held in galleries in London,

Glasgow, Berlin, Amsterdam, Singapore, Munich, New York and in Stockholm

and Copenhagen National Museum.

Her work can be seen in Museums of Modern Art in Delhi, Mumbai,

Chandigarh, Dusseldorf, Singapore, Bradford, Stockholm, Hiroshima, MOCA

LA, Peabody Boston, Asian Art Museum San Fransisco and Victoria and

Albert Museum London.

She has been extensively written about filmed, invited to various

countries and awarded, including a gold medal in VIth International

Triennele 1986 in Delhi. She was commissioned by Hiroshima Museum of

Modern Art to execute a large work for its permanent collection for the

50th anniversary of the Holocaust in 1995, and by Bangalore city and the

city of Hamburg to do large non-commercial murals in public spaces.

Since 1981 she did three large non-commercial murals in Delhi.

Today her paintings support several projects for the underprivileged,

including free vocational training in the Academy of Fine Arts and

Literature of which she along with her mother the renowned writer Ajeet

Cour, is the Founder Member. She supports a leprosy home in Ghaziabad,

and ration projects for poor and old widows.

-===========================================

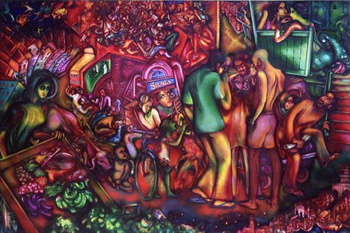

Arpana Caur paints

from her heart, and nowhere is this more evident than in her paintings

that celebrate the life of Guru Nanak. Arpana is a devout member of the

Sikh community, for whom the religious and ritual activities of the

gurudwara are central to her life. Her faith has sustained her through

national and personal tragedies––and it has given her spiritual

fulfillment that is expressed so directly and sincerely in her art. Sikh

topics are by no means the sole form of artistic output for Arpana, who

has painted since she was a young girl. As she herself has stated, “I

have always been interested in very hard social issues…and the problems

between the haves and the have nots…if you are a painter how do you

resolve the socio-economic gap?” i These are rhetorical statements and

questions; however, they pervade Arpana’s life and infuse her art with

refreshing sincerity rarely witnessed in the post-modern world that is

driven by critical theory. It is, in fact, this spiritual yearning and

commitment to preserving Sikh culture that brought Arpana’s work to the

attention of Dr. Narinder S. Kapany––they are kindred spirits in their

humanity and generosity.

Click images to view gallery

Arpana was born in Delhi in 1954, seven years after Partition.

Her family like millions of others had been uprooted from their home in

what is now Pakistan, and made their way down to Delhi in India. She

grew up in a world that was torn apart by communal dissension. Her

grandfather, a physician, tended to the poor and the homeless, and as a

young girl Arpana went with her mother to distribute rice, food and

blankets to the destitute. Thus she grew up in an atmosphere of

selflessness that would provide the background for her creative energy.

The stories of Guru Nanak, of Sufi saints, of the Buddha, and of

Sohni-Mahiwal occur throughout her oeuvre, as does the theme of

contending opposition in her series of paintings entitled Between

Dualities, in which the continuum that divides life and death, light and

darkness, enlightenment and oblivion is the cosmic joke, and time is

the metaphor for the universal soul.

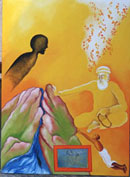

In Arpana’s painting Immersion/Emergence, the duality expressed is

that of before and after, of searching and finding, and of ignorance and

knowledge. In this diptych she evokes the idea of duality in the

miraculous experience that Nanak underwent when he retreated from the

world and was submerged under water for three days in 1499 at the age of

30. When he reemerged he uttered some of the most profound verses on

the oneness of all beings. As with many myths and legends, heroes must

undergo ritual separation, isolation and initiation in order to become

inspired, mature leaders. Nanak’s immersion provides the catalyst for

his revelation and insight that he expressed as Ikk Oan Kar (the One

Divine Being)––there are neither Hindus nor Muslims, only Humans. This

profound enlightenment provides the humanistic keystone for Sikh

culture. In the painting on the left Nanak is submerged in the watery

depths; he is described in blue, the same blue of the waves that wash

over him. Blue symbolizes the infinite and contrasts with the intense

red background, the color of passion, power and blood; these are the

colors that become the transformative force that enters into Nanak’s

being after which he is enveloped in the golden glow of joy and

enlightenment, as he rises above the waters.

Arpana works in series, often repeating themes in diverse ways. In

her triptych entitled, Immersion, Emergence, 2003, she describes Nanak’s

spiritual quest in a powerful set of paintings set against a dense

black background.ii In this triptych the element of narration encourages

the viewer to follow Nanak into the waters and sit with him in his

submerged state as he fingers his rosary, before emerging at the top of

the right painting. The darkness of the paintings castes a spell giving a

timeless quality to the period of Nanak’s immersion when the world

itself seemed to die.

The Golden Saint is a parable of good versus evil, of positive versus

negative, and of playing with the complementary opposing forms of

dualities, that records an episode that occurred in the Punja Sahib,

wherein Nanak prevents a mountain from crushing him by merely holding up

his hand. This is also a theme that Arpana has painted several times,

and one that is derived from 19th century miniature paintings. Here

Nanak robed in brilliant gold is showered with cascading flower petals

as he holds out his right arm and pushes against a mountain top that is

cleft by a blue running stream, over which hovers the ghost-like shadow

of a man. Arpana’s paintings are inspired by the nineteenth-century

miniature tradition of the Pahari styles of the Punjab Hills. They

include the bold Basohli school, and the romantic Kangra and Guler

schools that produced some of the most lyrical paintings in Indian art.

Here the finger-like extensions of the rocky mountains are seemingly

joined in the pious namaste mudra (greeting gesture), that recall the

highly stylized slopes and colorings found in early Pahari paintings. It

is as if they have recognized the great spirit of Nanak and are

imploring him for forgiveness. The small figure of a woman in the inset

red-bordered painting holds her hands out towards Nanak, echoing the

sentiments of the mountains.

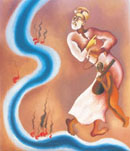

Wherever water flows it carves its way through terrain, dividing and

separating. Arpana uses water in many of her paintings in a similar way

as a formal device to divide her compositions. In the highly original

painting of Dancing Nanak, the sinuous lines of the blue river of life

are echoed in the curves of Nanak’s dancing body. Flames erupt from the

curves of the river like festering sores, reminding us of the eternal

duality that exists between fire and water. They also remind us of the

continuing tensions in the Punjab, the region of the five rivers that

throughout its history has been an area that has witnessed waves of

invading forces making their way down into the rich plains of India.

This same area witnessed the greatest transmigration of people in the

world’s history in 1947. It was a tragic event that continues to be

played out today in the political tension between India and Pakistan,

and Arpana inserts both the ambiguity and the duality of the continuing

political tensions into this painting of Nanak. The joyous dance of

Nanak, who danced in the way of the mystic Sufis to express his

spiritual devotion, is tempered by the flaming river––a reminder of

the insolvency that can overwhelm the human spirit. In the Shivaite

context the dance becomes the catalyst that destroys ignorance and the

demonic powers of darkness in order to restore life. Fire burns,

destroys and cleanses in order to bring forth life. Water also possesses

these dual powers of destruction and creation. In Arpana’s painting the

rhythm of the dance gives visible energy to Nanak’s joy and his sense

of hope.

Endless Journeys is a series of paintings that depicts Nanak’s

wanderings throughout the Punjab and his pilgrimages to Hindu and Muslim

sacred places, spreading the message of One God (ikk oan kar), the

equality of all men, the rejection of the caste system, and the futility

of physical existence. He is accompanied by his two faithful followers,

Bala, who was Hindu, and Mardana, a Muslim who played the rabab (lute)

as music for Nanak’s devotional songs. In one painting three large

footprintsiii enclose the three wanderers: Nanak robed in gold walks

with his staff, Bala follows with a water bottle, and Mardana walks

behind clasping his rabab.

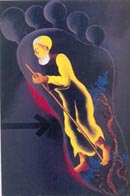

In the painting owned by Dr. Kapany, Arpana has drawn one large

golden footprint that appears to float in the firmament. Enclosed within

it is the radiant figure of Nanak walking with his staff. His

companions are no longer with him; he walks alone, intent on his quest

to spread his teachings.

In an almost identical painting entitled, In Bleeding Times, 2002, the

golden-robed figure of Nanak continues to stride forward, but now the

footprint is black. It is backlit by an ominous red glow as it floats

against a dark grey-black background. An even blacker arrow impedes

Nanak’s progress.iv It seems that communal tensions and violence will

never cease.

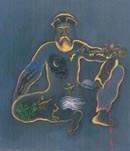

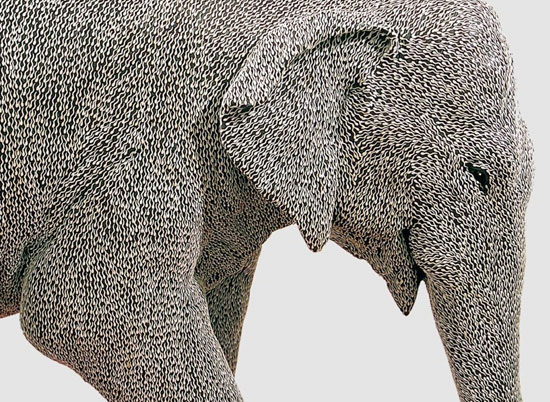

The reality of reoccurring warfare is expressed in Arpana’s iconic

seated figure of Nanak.v In this magnificent painting, as also in the In

Bleeding Times series, Nanak is seated in the posture of royal ease

with one leg bent vertically at the knee. His body floats upon a black

background and is contoured by a golden glow, inside of which soldiers

are fighting each other and hunting animals; blood is pouring from the

lifeless carcass of a tiger. Within Nanak’s right arm is the tree of

life with its blue leaves, the same tree that appears in the footprint

paintings of Nanak’s peregrinations. The stylistic tradition of painting

figures within figures, and figures formed of figures, is one that was

popular during the period of the Deccani Sultanate in the 17th and 18th

centuries. Then it was more of a visual conceit and a decorative

conundrum. Arpana has exploited this normally playful approach to imbue

her rendering of Nanak in the fullness of his compassion.

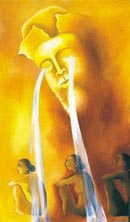

At the heart of Guru Nanak’s life and teachings was his consummate

sense of humanity and compassion. In her painting entitled, Compassion,

2002, the large, golden head of Nanak appears from the firmament like

the rising sun. Pouring from each of his eyes like waterfalls are two

streams of water that bathe three seated female figures below. In his

great compassion, Nanak is shown bathing away the sins of the world in

order to restore life and hope. The small figures are Arpana, who is

herself wholly embraced by the love and teachings of Nanak. This

painting, perhaps, more than any of the others speaks to Arpana’s own

sense of being Sikh. In a series of paintings that has celebrated the

miraculous and legendary life of Nanak, Compassion, brings the Sikh

experience into the present and into the personal and private sphere of

experience.

Arpana lived through the riots of 1984 and witnessed the horrors of

communal hatred that was perpetrated upon the Sikh community. Her

passion and compassion rise out of her own experiences and as a result

her art rings with great empathy for the condition of mankind. In Wounds

of 1984, Guru Nanak stands half naked, half robed in a white cloth,

again against a black background that castes the pall of endless night

over the painting. He is watched by figures to the left who peer out of

compartment-like buildings. But the question remains: Who is the

standing figure? Is it Guru Nanak? Is it Arpana’s grandfather who fled

with his family from Pakistan to India in 1947, as millions of others

did? Or, is it Everyman? In the right panel, a seated woman, Arpana,

holds up a blood-stained cloth that flows across the canvas like a

silver river.

Arpana’s use of color in her paintings sets up moods that encompass

the whole range of human feelings from ecstatic bliss to despair that in

turn draw upon rasa, aesthetic emotional sentiments that are

experienced upon seeing a moving work of art, hearing sublime music, or

being stirred by the exquisite movements of dance.vi In her painting of

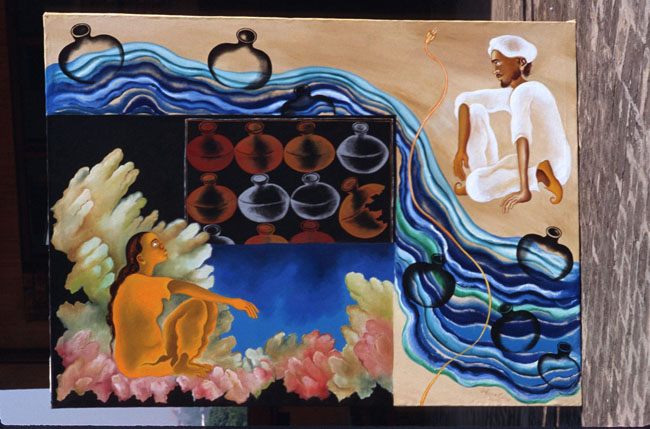

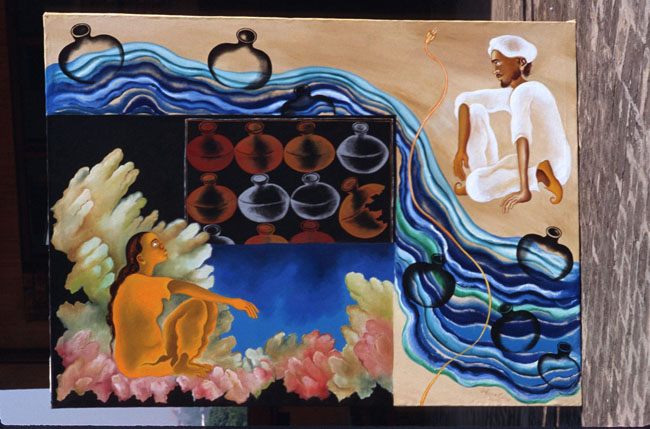

Sohni Mahiwal that is in Dr. Kapany’s collection it is the vibrant

palette that immediately draws the rasika, the viewer, into the world of

Sringara Rasa, the first and most important of all the rasas. It is the

rasa that expresses the depth of feeling between two lovers. It is the

passion of the human heart for the divine. It also expresses

transgressive love for the forbidden or the unattainable. Sringara Rasa

is manifested in two ways, that of sambhoga, love in union, and that of

vipralambha, love in separation; it is the latter that is so clearly

portrayed in this painting of the two young lovers, Sohni and

Mahiwal––the longing that occurs when lovers are apart. This is

described by Sufis as ishq majazi, human love, for ishq haqiqi, love for

God. It is the unrequited universal love of the ages of Laila and

Majnu, of Heer and Ranjha, of Sassi and Punnu, and of Romeo and Juliet.

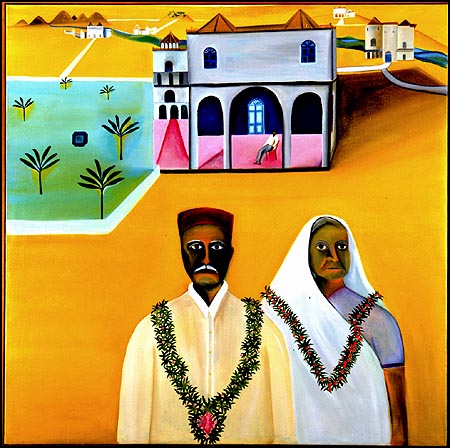

Sohni and Mahiwal were from two different worlds, she was the

daughter of a potter, he was a rich trader from Bukhara. They fell

passionately in love with each other. Mahiwal gave up his lucrative life

and became a buffalo herder just to be close to Sohni. Inevitably their

love for each other was discovered and her parents hastily married her

off. At this turn of events Mahiwal renounced the world and became a

faqir, hermit, living in a small mud hut across the Chenab River. At

night, under the cover of darkness, Sohni would come down to the river

to meet Mahiwal who had swum across it to be with her. Mahiwal injured

himself in his selfless drive of love for Sohni, so she started to swim

across the river with the aid of a clay jar; predictably, her absences

at night were discovered, and one night her sister-in-law followed her

to the river. The following night the sister-in-law replaced the clay

jar with an unbaked jar that began to dissolve as soon as Sohni entered

the water with it, and in mid-stream she drowned. Mahiwal was so

distressed at seeing Sohni’s death that he plunged into the river and

drowned as well, and so ultimately this ill-fated affair came to naught.

In Arpana’s painting the lovers’ worlds are separated by the

fast-flowing blue and green waters of the Chenab that divide it

diagonally. Transparent jars outlined in black float upon its surface as

reminders of past trysts. Mahiwal, dressed in white, sits on the

sandy-colored shore patiently waiting in the upper right hand corner.

Yet it is Sohni that captures the imagination. She sits in the lower

left corner of the painting, gazing over the river to Mahiwal. The rigid

rectangle in which she sits acts as a constraint and a warning. The

rows of jars against the black background add further ominous tones,

emphasized by the broken jar that offers a premonition of what is to

happen. Yet it is the crystal-like fingers that enclose Sohni that

electrify her emotional state. In icing pinks, jade greens and creamy

yellows the fingers of the crystals enfold her, opening up to reveal her

radiance like an embedded jewel. These forms can also be read as clouds

that will transport her to her beloved, if only in her imagination.

The Punjabi legend of Sohni and Mahiwal is the source of folksongs,

plays and films based upon the life and love of a real potter who lived

some five hundred years ago in Akhnoor by the Chenab River that runs

through Jammu and Kashmir. The intensity of the love that is expressed

in this romantic tale is that of vipralambha, love in separation. In

fact the formal aspects of the composition serve to emphasize the

tensions of the inaccessible. Even the unplugged electrical cord that

winds up along the surface of the painting, like a snake rising from its

master’s basket, seems to be seeking a socket that would allow the

magic to happen, yet further serves to separate Sohni and Mahiwal. This

is an incredibly powerful painting of the depth of human love for the

divine, and the risks that are taken to seek fulfillment.

It is hard to extricate the painter from the paintings in the art of

Arpana Caur.vii She lives her life as one called to profess her faith in

Sikhism through her art and through her enormous generosity and

selflessness. Her inspiration and her paintings are a guide for all of

us.

Arpana Caur, a Contemporary Indian Artist was in

born 1954. She is a distinguished Indian painter and has been exhibited

since 1974 across the globe. Her solos apart from Delhi, Mumbai,

Calcutta, Bangalore and Chennai have been held in galleries in London,

Glasgow, Berlin, Amsterdam, Singapore, Munich, New York and in Stockholm

and Copenhagen National Museum.

Arpana Caur, a Contemporary Indian Artist was in

born 1954. She is a distinguished Indian painter and has been exhibited

since 1974 across the globe. Her solos apart from Delhi, Mumbai,

Calcutta, Bangalore and Chennai have been held in galleries in London,

Glasgow, Berlin, Amsterdam, Singapore, Munich, New York and in Stockholm

and Copenhagen National Museum.